Evolutionary Genealogy

Conventional genealogy describes the descent of members of a family or a group of closely related families. This is usually depicted graphically by a family tree, which typically goes back only a few generations, but only because of lack of information. The family tree of course really keeps going, to great-great-great grandparents, great-great-great-great grandparents, and so on.

In fact, if you keep going back in time, any family tree will eventually join up with the family tree of every other person on the planet. You are related somehow and in some way to every other human on the planet, living or dead, whether it be Martin Luther King, Madam Curie, Charles Darwin, Genghis Khan or Queen Victoria.

In fact, if you keep going back in time, any family tree will eventually join up with the family tree of every other person on the planet. You are related somehow and in some way to every other human on the planet, living or dead, whether it be Martin Luther King, Madam Curie, Charles Darwin, Genghis Khan or Queen Victoria.

Even without a family tree, genetic studies are able to broadly suggest how any two humans are related. Pick any person on the street. Travel far enough back in time and you will meet the common ancestor the two of you share, which makes that person your cousin. If the common ancestor is just two generations in the past (in other words, a shared grandparent), that person is your first cousin. If the common ancestor is three generations in the past (in other words, a shared great grandparent) that person is your second cousin. That person's child would be your second cousin, once removed, and their grandchild your second cousin twice removed. If the common ancestor happens to be 30 generations in the past (in other words, a shared 28-greats-grandparent) that person is your 29th cousin.

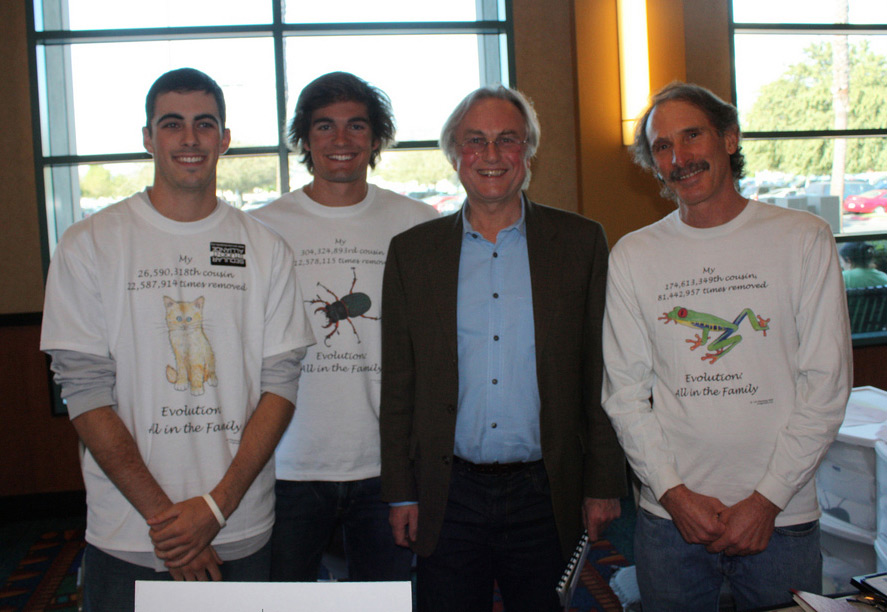

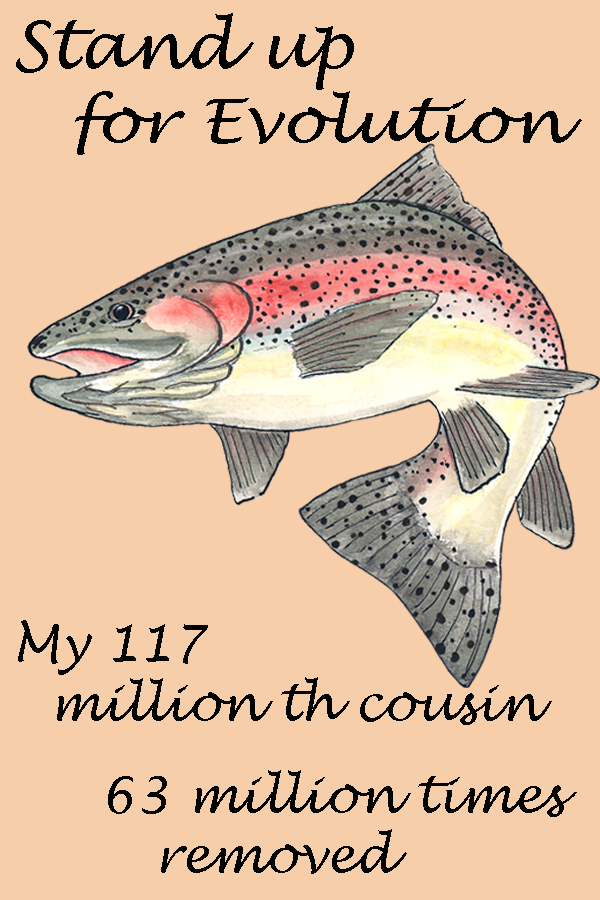

‘Every individual living thing is your cousin. And approximately your xth cousin, n times removed.’

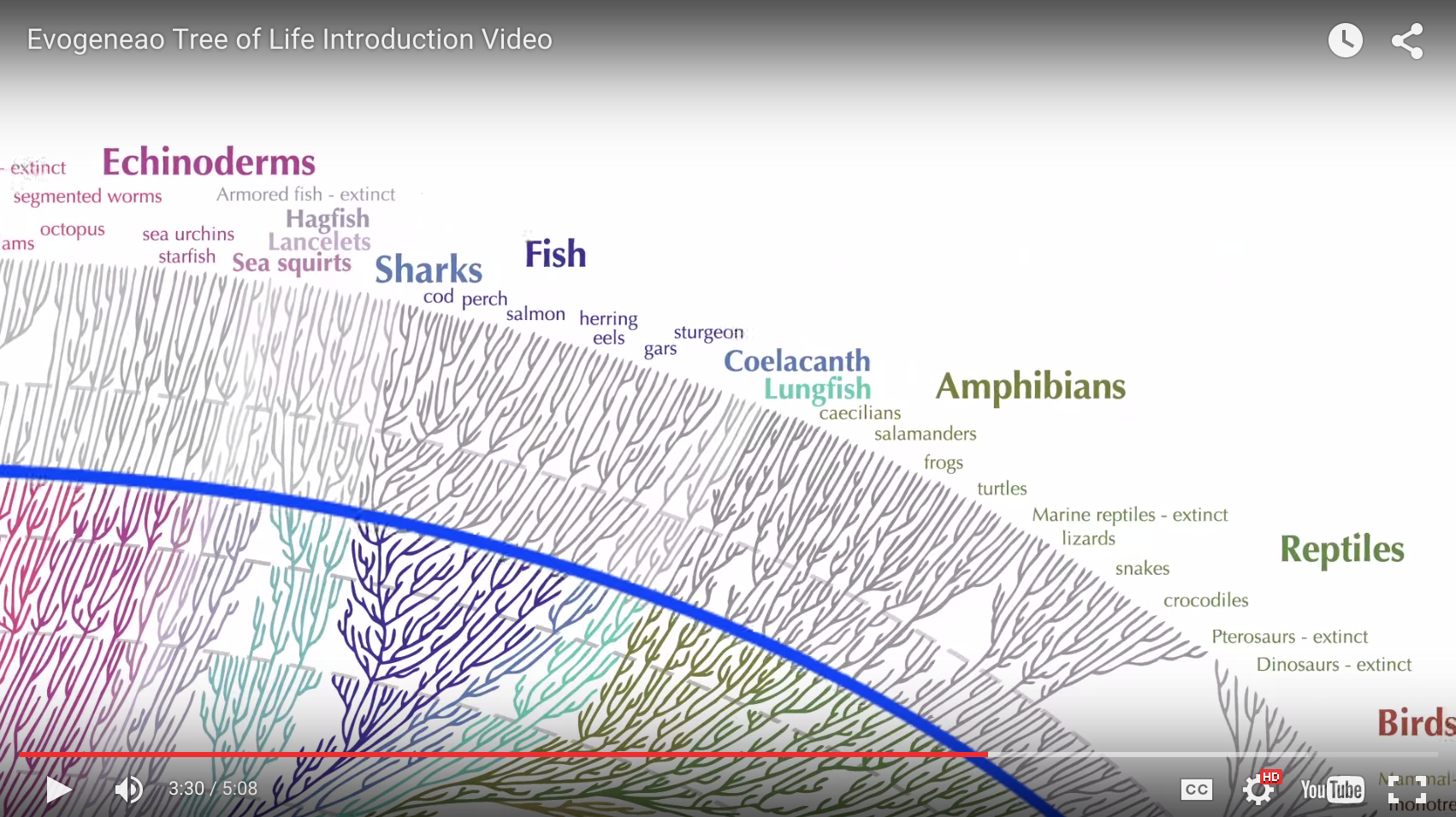

The Tree of Life

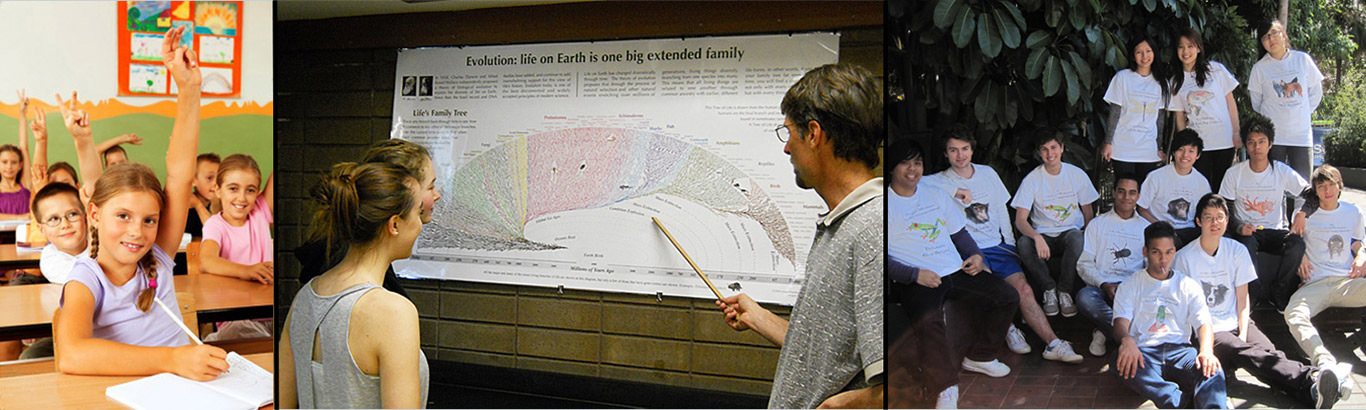

The Evogeneao Tree of Life is like a standard family tree; the only difference is that it goes back millions of generations, back to the start of life on Earth. Just as in a standard family tree, the genealogical relationship between any two living things, past or present, can be described. Every living thing, whether it’s a bird, a tree, or a dinosaur, can be described as your xth cousin, n times removed.

Calculating your genealogy with other life forms

To make an estimate of the cousin and removal relationship between you and any other living thing, count up the generations back to the common ancestor on both lines of descent. This sounds easy, but is complicated in practice. First, make an estimate of the number of generations along the human line of descent back to the common ancestor. Use commonly accepted estimates for generation times of humans, as well as those creatures likely to be templates for our successively older ancestors; chimpanzees, other apes, various species of monkey, treeshrews, and so on.

Second, apply the appropriate generation times to time intervals defined by ages of meeting points with common ancestors. For example, between 27 and 42 million years ago, that is, between the approximate ages of our common ancestors with old world and new world monkeys, respectively, the ancestor on the human line would be assumed to be a creature somewhat similar to a new world monkey and thus have an average of ten years per generation. In the absence of direct information on generation times for a species, it can be estimated by noting average life expectancy in the wild, years to first birth, and average age at last birth. With this sort of information, one can pick a time midway between years to first and last birth to get generation time.

Third, calculate the number of generations along the non-human line of descent back in time to the common ancestor with humans. Helpful data would include evolutionary history, generation times of the modern organism, and the generation times of modern organisms likely to serve as templates for intermediate forms along the evolutionary path to the common ancestor with humans. In the absence of such data, generation times can be estimated from likely body size; smaller forms generally having shorter generation times. If no data are found on forms intermediate between the modern species and the common ancestor, one can evenly distribute the change in generation times between points with data. Generation times should be the same along the human and non-human lines of descent at the point of common ancestry.

The same process can be used to estimate cousin and removal relationships between any two organisms; a bat and a cat, a salmon and a butterfly, a coral and a rat. The interactive Evogeneao Tree of Life Explorer illustrates this in a fun way all students of evolution can enjoy. https://www.evogeneao.com/en/explore/tree-of-life-explorer

An excellent source for animal generation times is http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/

An excellent source for times of common ancestors is http://www.timetree.org/

Other helpful sources are listed on the bottom of our In the Classroom page

Our Evogeneao cousin and removal estimates encompass a wide range of organisms from humans to bacteria. Samples of the graphic technique used to post data and make Evogeneao cousin and removal calculations are shown below.

Note: The cousin relationship in formal genealogy is determined by which line of descent has the fewest numbers of generations to a common ancestor. In the chart of relatively recent cousins shown above, it is always the human line of descent. But for some other species, the non-human line of descent has the fewer number of generations, which therefore determines the cousin relationship. For example, frogs (because of their large-sized, and therefore long-lived, amphibian ancestors of the late Paleozoic), are approximately 98 millionth cousin to humans. If instead the cousin relationship was determined on the human line of descent, (frogs were determined to to have a larger number of generations to the common ancestor), frogs would be approximately 151 millionth cousins to humans. This aspect of genealogy can be confusing, but if one bears in mind how the cousin relationship is determined, it will make sense.

The reader will certainly see that there is unavoidably a potentially huge error in any single estimate used to determine a cousin and removal relationship. The age of the common ancestors, their likely forms, and their generation times may be poorly known. However, it is at least reasonably likely that errors cancel each other out and that the overall result yields a reasonable estimate. The goal is not to determine an exact relationship, only to get reasonably close to illustrate the point. Science can determine that our common ancestor with chimpanzees is between our 150,000-greats-grandparent and our 400,000-greats-grandparent. But the real point is that that individual chimpanzee at the zoo looking you in the eye has a genealogical relationship with you, such that the chimp could be something like your two hundred and eighty-three thousand three hundred and fifty sixth cousin, eleven thousand seven hundred and twenty times removed.

Note that, except for close relations, there is NOT a unique genealogical path between two organisms. It is much more likely to be a tangled web of interrelationships. For example, a husband and wife might be, exactly, fifteenth cousins twice removed, as well as thirteenth cousins thrice removed, depending on which tortuous path of ancestors one followed back to the last common one. But as long as this is understood, the exercise of counting generations back to a common ancestor is really an eye-opener for all who make the journey.